Let's start with the untimely deaths

If you subtract the murdering and the heroing and the poeming, there's really not much left.

.

022) The Life and Death of King John by William Shakespeare, finished February 28

Another very strange play. I know I say this every time I read a new one. I'm starting to think Shakespeare might be a good writer. Although he deals with similar themes and milieus and motifs, each play is distinct.

King John is arguably the most forgotten of the plays in 2024 (apparently this, too, is the Victorians fault) and I'll admit I'm a bit flummoxed as to what it's all about. John is supposed to be a terrible king and he is terrible. But the play doesn't really treat him as terrible. Even when he's ordering the death of a child, he doesn't seem like and he turns out much differently then, say, Macbeth or Richard III when they do the same. The role of the female characters is fascinating. They dominate the first half then they all die offstage in an instant. The appearance of Prince Henry is only the most perplexing of the sudden appearances. The early battle feels like the sort of battle that should appear at the end of any other play. The role of the bastard boggles. In short, very fun! Excited to read more about it and to talk about it with my classes!

three days

022) Might Jack and the Goblin King by Ben Hatke, finished February 29

More Hatke goodness!

I'm guessing this book is skewed older given some so-so language but intellectually we're in the same place.

one sit

023) Chronicle of a Death Foretold by Gabriel García Márquez, finished March 4

Considering how short this book is, how did it take so long to read? I didn't feel like I dallied, but everything from rain to roadtrips got in the way.

Chronicle reminds me of Wilder's The Bridge of San Luis Rey: someone has died and someone else is doing research, putting together the story and trying to figure out what it all means. Chronicle was released fifty-four years later and although some very lazy searching doesn't suggest a connection, I can't help but to wonder if ol' Gabo's responding to Thornton Wilder's novel. The researcher is now an insider, rather than an outside. It focused on one person and their actual community network verses looking at several people and hoping to find metaphysical connections between them. I dunno. But it feels likely.

(Yes, even though it's based on a true story. Bigshot award-winners must read each other, right?)

Anyway, it starts "On the day they were going to kill him" (trans. Gregory Rabassa) and ends with his murder. Although the timeline is far from straightforward, shooting years into the past and future and all over the day in question, the basic setup of nonsuspense is clear from go. The book will end with the murder of Santiago Nasar. And what a gruesome murder it is.

The narrator seems to think Nasar's a solid fellow and the town generally seems to agree although, when it comes to the girl working at his house, he does seem to have the sort of wealth that leads to men saying when you're a star, you can do anything. Grab 'em by the pussy, for instance.

But that's hardly the most alien element to me reading this story as a 2024 American. The matteroffactness of honor killing, for instance, is even more shocking. But it's this very simple-strangeness that I appreciate the most. I believe in this world he's created. And it has its marvels and charms. But hoo. I wouldn't want to live there.

But what a tragedy---for everyone in town to know you're about to be murdered. Everyone except for you.

somehow like six weeks

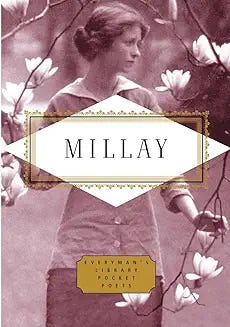

024) Millay by Edna St. Vincent Millay, finished March 6

I recently read an article about Milly and it made me realize that aside from the figs, I didn't know much about her. So I picked a volume from the library and I read it.

And I really liked it! I did cotton to her earlier work more strongly, but I did find other favorites like "Wraith," "Burial," "Lament" (which has an interesting echo in "The Ballad the Harp-Weaver"), and "Exiled."

Also, I sent a research request to the Schulz Research Center because these lines from her 1919 play remind me of something from 1959:

PIERROT Don't stand so near me!

I am become a socialist. I love

Humanity; but I hate people. Columbine,

Put on your mittens, child; your hands are cold.

We'll see what they say.

In the meantime, color me sad Millay isn't yet rediscovered by the women and youth of Gen Z. I think they'd really like her.

nine weeks but really only the weeks on either end of that span

025, 026) The Life and Death of King John by William Shakespeare, finished March 6, 8

Always interesting to see how classes will take to a play I've never taught before. In general, I fear the histories just because . . . just because. Even though Richard III is the only other one I've taught and I love teaching Richard III. Anyway, King John is an early play and Shakespeare's not quite Shakespeare yet, but it does have some great moments. The plot's a little hard to follow and a bunch of characters talk too dang much but, as always, we're latching on. There's more confusion that usual but I'm feeling positive it'll all work out before the test. We'll see!

two weeks max

027) Murder Book by Hilary Fitzgerald Campbell, finished March 11

I found this book because I loved Campbell's essay in The Peanuts Papers and was learning more about her. I also like her New Yorker comics.

The book is okay. I daresay it was a good learning experience for her. By the end of the book she's gotten better at panels and guiding the eye, etc. But it's a pretty long book about being obsessed with true crime. And while I enjoyed every page, I'm not sure it needed to be so many pages. The epiphanies she arrives at are pretty mundane. Plus, all her women have the same face. And there's some editing issues, eg, one character's skin keeps changing color. Or tone, I suppose, this being a black-and-white book. And, um, did we really need to see her on the toilet So Many Times?

Anyway, solid proof of concept. I think her next one will be better.

maybe ten days

028) A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller, Jr.

This classic Fifties work of science fiction is about a world after our world ends. A nuclear holocaust happened—my guess is sometime in the 1960s—and the novel opens 700 years later. It's an almost medieval world. Our main characters are Catholic monks striving to maintain the shattered (and burnt) remnants of human knowledge so that someday, when people care again, that knowledge will still exist. They remind me of the monks in How the Irish Saved Civilization. And rightly so.

But hold your hat! At the end of part one, we zoom forward another 700 years. And at the end of part two, another 700 years.

In other words, Leibowitz is like The Fifth Head of Cerberus in that you have three novellas. I think each of these could stand on their own but each is so clearly informed be the one before, it's hard to say. You read them out of order and let me know.

In some senses, in terms of normal expectations for a novel, this can be a frustrating book. Main characters die and we don't know what happens until 700 years have passed. That sort of thing.

But of course those great distances allow for the examination of hefty questions like: what do we learn from the past and what is just being human? does booklearning actually make us any wiser? et cetera.

And the constantly present lens of Catholocism allows for a deliberately contemplative and multiplyingly provocative look at the many questions and issue the novel raises. Which isn't too say it isn't fun to read. It's crazy fun to read.

The reason I finally picked it up is because I finally had a group of AP Lit students choose it off the dystopia list for the group project. (Incidentally, though often described as dystopian, I'm not so sure it is. I'll be interested to see if they think it should stay on the list.) Since I wanted to have my own experience with the book, I've been hurrying to get it read before they do. I just beat them.

Anyway, I was worried in the early pages that they would be bored. But by page forty or so, I'd lost that worry. In fact, when I told them this and talked about the first few pages, they thought they sounded fascinating. And they've been devouring the book. I'm excited to see what they do with it.

Anyway, three times it's placed for the Locus for best sf novel of all time. Those votes weren't spaced 700 years apart, but still. Impressive.

about two weeks

029) The Last Hero by Terry Pratchett and Paul Kidby, finished March 15

Something about fantasy books with realistic paintings throughout always turn me off. I think particularly so when the author is Terry Pratchett. I'm skeptical a painter can be appropriately funny. Or, more accurately, appropriately witty.

But you'll see I added Kidby's name to Pratchett's uptop and that's because he earned it. Not only is appropriately witty, he's also working in tandem with Pratchett to tell the story. By no means is this a comic, but, in the same manner, the text and the images are working together to tell the story. Neither stands on its own.

As a Pratchett novel, it's short. But it feels just as rich. And the art is spectacular. The image of our protagoists standing on the moon watching Discrise with the frame dominated by the enormous face of an elephant . . . breathtaking.

about five days

030) Karen's Roller Skates by Ann M. Martin and Katy Farina, finished March 18

one sit