Discover more from Thubstack

.

This go-round, I check off another LDS writer I've never read, spend some more time in the black-and-white era, travel below ground, to midcentury suburbia, the depths of the music industry, the distant future, and a folkloric past.

It'll be a fun trip. Thisaway, friends!

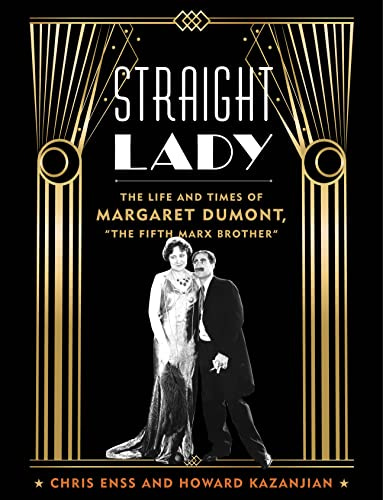

044) Straight Lady: The Life and Times of Margaret Dumont, "The Fifth Marx Brother" by Chris Enss and Howard Kazanjian, finished April 25

So I really loved this book. I loved learning about Margaret Dumont's early years and behind the scenes with her and the Marx Brothers. Tons to enjoy here. That said, this is a really weird book.

The authors have done tons of research and it's not unusual to have pages of long quotations (a page or more) strung together, often redundantly, from period newspapers and the like. That's kind of weird. Fun and I liked it, but peculiar.

Once she starts working with the Marx Brothers, it's really more of a Marx Brother's biography with constant glancing over to see what Miss Dumont's doing. Literally, there are chapters that are about all the movies the brothers are making without her, then a page listing the titles of the movies she'd been in. I mean—I get it's probably the Marx Brothers that are gonna get people to pick up the book, but this is still supposed to be a book about Margaret Dumont. So that was weird.

The last chapter and a half was suddenly riddled with errors. Misspelling chaise longue is one thing (who among us has not?) but misidentifying an image as being from one movie when it's from another is a problem. Though, now that I think about it, perhaps not as big a problem as earlier in the book where in two pages they swapped whether "Duck Soup was the highest grossing film of 1933. It didn't do as well as Horse Feathers, but it performed well at the box office." (76) or "Duck Soup...was no as big a hit as Paramount hoped it would be. Horse Feathers had been the highest grossing film for Paramount in 1932. Duck Soup was sixtieth on the list of top income-earning motion pictures in 1933. Audiences weren't enthusiastic about the movie." So that was weird. And worrying.

In short, for all I dug about the book (which was plenty), it has some of the same variety of problems I complained about after reading Unmask Alice. Publishers aren't doing their job.

That said, I now know lots about Margaret Dumont (first Daisy Dumont) and I'm glad I do. She started in theater young; she was beautiful and had an astonishing singing voice and comedic chops. She was so skilled she made it into higher theater even given her low roots. She was happily married a rich guy for eight years until her father-in-law and his new young wife cut them off and her own husband died, sending her back to the boards.

Obviously, there are more details, but Margaretwise, her early decades were my favorite part of the book. Perhaps I enjoyed reading most about she and the Marxes traveling the country refining jokes and pratfalls, and perhaps I was most frustrated with the MGM years (the same MGM years that frustrated me while reading about Buster), but I signed up to learn about Margaret Dumont and that I did and I am glad.

a week or maybe more

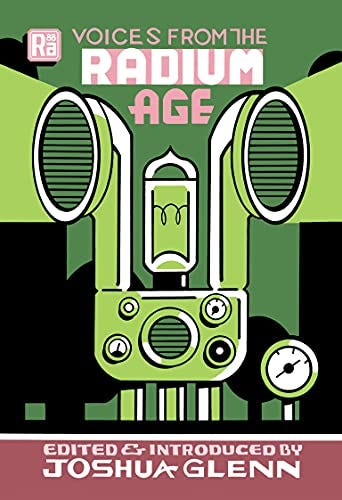

045) Voices from the Radium Age edited by Joshua Glenn, finished April 26

Voices from the Radium Age is the first volume of a series being published by MIT. Editor Glenn has named the late 19th- / early 20th-century, pre-"Golden Age" range of science fiction the Radium Age and it's a solid name. And nothing works like naming something to bring it to life.

The stories here are uniformly terrific but engaged in very different tasks. Me, I found the book because someone on Twitter was asking for short-book recommendations and some one mentioned the story by E.M. Forster. A good friend of mine wrote his dissertation on Forster's fantasy, so I'm overdue to read some. Or, failing that, his one piece of science fiction. This collection was the only option at my library, so I picked it up. I doubted I would read anything else (I was uncertain I would ever read Forster) but I started with Glenn's introductory matter in a slow moment and he sold me. I was gonna read the entire thing. And so I have.

(Worth mentioning that the first thing that made me certain I would take the book seriously was its Seth cover. Covers do matter.)

Sultana's Dream (1905) — Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain : A decade before Herland, Ladyland. Ladyland is an Indian feminine utopia and more sciencefictiony than Gilman's. But it also takes place within a dream. I do love the idea of pipes carrying the heat of the sun, though.

The Voice in the Night (1907) — William Hope Hodgson : This feels like an episode of Suspense or something (surely it was adapted for radio?). Two men on a schooner approached by one man on a rowboat, unwilling to come into the light. One of the first fungus/human stories, so if you've been digging The Last of Us, you owe yourself this trip.

The Machine Stops (1909) — E. M. Forster : This is what I came for and it is startlingly current. People living homogeneous lives, engaged in meaningless media consumption. It's got a world-running A.I. Agoraphobia. Pride in ignorance, comfort in lacking courage. The story features a woman whose son is dissatisfied and this is barely comprehensible to her. Sure, it's a bit dated here and there, but with just a couple edits, you could easily believe this story is from this decade.

The Horror of the Heights (1913) — Arthur Conan Doyle : What if there are jungles of the air, far up above us, and we've been able to live in ignorance of them simply because we as a species have never flown above 30,000 feet? And the what happens when we finally do?

The Red One (1918) — Jack London : Glenn discusses this story as being racist beyond just having a racist protagonist, and no question that there are descriptions unpleasant to the modern ear, but London sticks with third-person-limited throughout. So it's hard to say for sure. My suspicion is that, like a lot of liberals, his feelings on race were corrupted by his embrace of eugenics. Anyway, racist guy is stranded on one of the Solomon Islands where the great god is a giant sphere of uncertain (but red) metal perhaps from space. It's lovecraftian stuff.

The Comet (1920) — W. E. B. Du Bois : This is the only story in the collection I'd read before, circa the summer of 2020, and my opinion holds. First, that it's a great mood piece and succeeds on both halves of its reckoning with both apocalypse and race in America. Second, that the ending makes no sense. Where did that woman come from?? And even if the text does provide an explanation I haven't found, it's still an absurd coincidence and DuBois shoulda looked harder for another ending. In my opinion. I just hate being thrown out of excellence at the last moment, even if the thing doing the throwing is thematically necessary to the author's moral.

The Jameson Satellite (1931) — Neil R. Jones : (Jones was born the year Forster wrote "The Machine Stops," which may give you a sense of the amount of time the Radium Age fills.) The first in a long series of stories, in which Professor Jameson dies in the last century yet whose body outlives the earth, letting his brain be resurrected by passing aliens to a metal body. I enjoyed it but I'll be the later stories have more adventure to them. I will say there's something about his space coffin and resurrection that reminded me of the mode of travel in Burroughs's Mars stories.

under a week

046)The Ballad of YFB by Aaron Brassea, finished April 28

This is a comic from 2010. The art is . . . simple. The writing is plain. It's an aesthetic.

It's about a crappy band that becomes a famous band which gets into a competition with a song-writing robot. The the lead singer gets back with his pre-fame girlfriend and . . . I think the robot kills him out of jealousy? I'm not sure.

two nights

047)Reynaud's Tale by Ben Hatke, finished May 3

Hatke's been hit or miss in my experience, but we can safely call this one a hit.

Each spread is a page of text and a page illustration. The illustrations are great, both now and folk, and the adventure has the calm forward momentum of myth.

The books seems to marketed as for kids but my library catalogued it as adult, and I think that's right. Nothing too scandalous, but some breasts and casual sexual relationship exist in fairy-tale matter-of-fact-ness.

An excellent book to sit down with and take a moment's pleasure.

one night

048)Superman: Up in the Sky by Tom King and Andy Kubert, finished May 5

I saw someone online call this the premier or greatest or best or finest or something Superman story so I thought I'd check it out. I get why people might thinks so. It has serious literary ambition. Although it holds together coherently as a standalone story, it's loaded with allusions to other takes on the DC mythos that will add resonance to those in the know. Some of those left me feeling a bit left out and also left me wondering if things I did not think were allusive might, in fact, have been. So although I appreciated the craft, the book left me feeling a bit cold, especially when other characters' appearances seemed purely gratuitous.

Until the final portion when this celebration about all that's great about Superman truly came together into evidence that what is great about Superman is truly great.

It's hard to let Superman actually embody all the things he's supposed to stand for and yet still tell a great story. How can someone both unbeatable and always good be made into an identifieable character? Haw can we be made to care about his quests?

And this story left out most of the plot, just showing us individual moments in great details. (Like I said, literarily ambitious.)

Yet somehow it all came together at the end into something genuinely moving and pure.

So kudos. Well done.

two days

049)Ramona and Her Father by Beverly Cleary, finished May 5

The 6yrold says she likes how she turned happy at the end and that her father finds a job.

While Mr Quimby does play a larger-than-usual role in this book, he's more the mise-en-scene than player. Not to say he doesn't matter as a character—her certainly does—but the book is driven by him losing his job in the first chapter and not finding a new one till the last chapter (which he does not begin before the book run out of pages). His stress is also increased by the girls pressuring him to give up smoking. In fact, the whole emotional fabric of the book takes its cue from Mr Quimby, which is something Ramona feels and sees but cannot thoroughly understand.

Plus, this is another world, economically and culturally. And the 6yrold was so surprised that Ramona prays and goes to church, which got me thinking: secularism is the assumed reality for kids in American children's literature. Especially generically white children's literature.

That seems narrow.

several weeks

050)Resurrection Row by Anne Perry, finished May 6

Anne Perry wrote a lot of books and they sold lots and lots of copies. I've never read one. But then she died and I came across this in a Little Free Library when I was without a book and so I figured the time had come.

This is the fourth in the Inspector Pitt series (1981) and, like them all, named after an actual London neighborhood. It's an apropos neighborhood to appear in the story as the mystery begins with disinterred bodies appearing and demanding an explanation.

The adventure takes us to high-end homes and to the most poverty-stricken corners of London. The story moves at a good pace and the era and location come to life.

I get why people like them!

I am curious how the good inspector and his wife came to be a match, but not enough to seek the book out. If I get lucky and an earlier volume falls into my lap, then we'll get our answer.

As it is, I have no read Anne Perry.

two or three weeks