.

If you stick with me to the end, we'll together take a trip to hell. En route, I am afraid we will see murders and imagined murders and ancient battles of the sexes. Are you strapped in?

.

103) The Sandman: The Doll's House by Neil Gaiman et al., finished September 14

This collection is a deliberate single story and it's a great example of what Gaiman is good at and what Sandman is good at. It has sex and violence, beauty and horror. It has fine lines and opportunity for the artists to play around. Fascinating characters both lovely and despicable, both knowable and inscrutable. It shows people and places that can otherwise be so easy to never see. Deliberately, accidentally, it hardly matters—we simply do not see. The pacing speeds up and down. Major characters take their place in both fore- and background. Minor characters as well. Meaning is suggested and then swayed away from.

He's found his rhythm.

almost a week

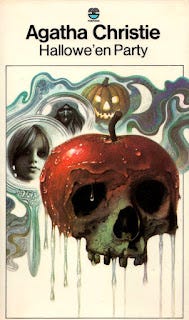

104) Hallowe'en Party by Agatha Christie, finished September 2023

The new librarian is attempting a book club with the teachers. I'm game. And the first book is this Hercule Poirot mystery, the movie of which I may have watched last weekend had I not begun the book instead.

I must say the trailer confounds me:

Wikipedia says the movie "transpose[s]" the action from the novel's bucolic village to Venice, but other than some water, a girl, and a friend of Poirot's who happens to be female, what to they have in common? The novel has no seance, no psychics, no locked-room aspect, no supernatural element of any sort, basically nothing that appears in the trailer whatsoever.

Some English townfolk in the '60s are preparing a Hallowe'en party for a couple dozen local kids. One of the kids is murdered at the party. Poirot is invited by his friend to investigate. He does. He wanders around the lovely countryside having conversations.

I still want to see the movie but I haven't much worry that reading the novel will spoil anything for me.

The structure of the novel was fascinating. It's a very slow burn. It really is just Poirot walking around talking to people. The last couple chapters add some suspense and propulsion but otherwise the entire runtime is cozy in the extreme.

Nothing like the trailer whatsoever.

Can't wait to see it.

I hope I enjoy it as much as the book.

But, if I do, I anticipate an entirely separate sort of enjoyment.

just over a week

105) The Sandman: Dream Country by Neil Gaiman et al, finished September 27

Short stories this time, including a couple of my favorites about an abused Muse and Shakespeare performing for actual fairies.

I will certain know if I hit an unread volume because they all come back to me as I read, even though it's been twenty years.

They're not all equally good but they are all good. Onward we go.

under than two weeks

106) Apples Never Fall by Liane Moriarty, finished September 29

I know the names of Lianne Moriarty's novels from prestige television adaptations and for some reason (petty snobbery?) I find that a turnoff so I never would have read this book were it not for the great pleasure it gave my beloved when her book group read it. I mean---she was having fun, people. So even though it's almost 500 pages, I picked it up as soon as she was done.

And folks, this is a solid piece of entertainment. Well structured, littered with terrific characters, plain but nonagressive points roiling beneath the service---enough to trigger all your layered pleasure centers.

For instance, it has a lot to say about what we inherit from our parents (like it or not) and sometimes it was frustrating how clearly we could see things the characters could not---but, well, that's exactly how people are. It did not make me believe in the characters any less.

As for the structure, I was just complaining about a book that attempted something similar; this one has perfect execution. There's no diminishment of suspense. I mean---I was convinced at one point of [redacted] only to discover [redacted] when I picked the novel back up the next day. What a delightful reading experience!

The opposing emotions this novel forces upon you prevents a simplistic reading of humanity. People are complicated. Yet Moriarty loves humans. You can tell. Even the clearest villain of the novel is treated with grace. Yet part of the reason for this is which character consists of the emotional and ethical core of the story. She's not a saint or anything but her presence---even in her failings and errors---makes everyone else better.

My mother plays tennis.

monthish but I think less

107) Paul Among the People: The Apostle Reinterpreted and Reimagined in His Own Time by Sarah Ruden, finished October 1

One of our Sunday School teachers brought some of the ideas in this text collected from printed interviews and podcast appearances. I went ahead and hunted down a copy because I was intrigued by some of the details about women wearing veils and such (all cut out of this episode) and I've been reading it on Sundays since.

First, Sarah Ruden is an excellent writer. Her company is very welcome as we take this journey, trying to understand ol' problematic Paul as his contemporaries would have understood him.

In short, almost all the things that drive us crazy about Paul in 2023 AD are because we don't know what the world was like 55 AD. The woman-in-veils thing, for instance. At the time, you weren't allowed to wear a veil unless you were wealthy or married. And not wearing a veil meant you were sexually available to men who felt like so availing. But when a woman comes to church? It doesn't matter who you are in the outside. In church, you can all wear veils. We are all the same here.

She similarly brings us into other aspects of Roman culture, revealing how our default assumptions don't really apply to Paul's acolytes' realities. He was not talking about anything like our world when he came out against gay people or seemed upsettingly ambivalent about slavery. We don't even understand what he meant by words like "father" or "child" or "love" or "faith." Two thousand years of domestication has resulted in doctrines that make us think this is a wolf:

I really can't recommend this book highly enough to any layperson who has been frustrated by Paul and wants to understand how this grumpypuss managed to craft the Christianity we still celebrate today.

Ruden's expertise in, as she puts it, "the literature of food, clothes, sex, family squabbles, petty commerce, local politics, and staying out of the rain," allows her to bring in her own translations from a world so different from hers that you will never read more shocking, upsetting, horrifying stuff in a book I read almost entirely over a series of sabbaths.

His world was not our world.

Understanding that helps clarify just what Paul was getting at.

And how devastatingly radical it was.

Ultimately destroying the Greco-Roman world and building one where such concepts as freedom and equality, the Enlightenment, democracy—our entire modern ideal—could take seed and grow.

Paul showed us the ideals we are upset he doesn't meet, like self-righteous teenagers discovering morality and holding it up to the adults we know.

It's an old story.

Hey—we all still think as a child and see through glass darkly. So perhaps we need to read Paul because we are more like him than we think.

three weeks

108) Cymbeline by William Shakespeare, finished October 5

What a weird one this is. It's like it takes all the things I find strangest about Shakespeare's plot and characters, sticks them all together, then renders them even more absurd. Innogen is a reasonably likeable character but all the other leads are absurd caricatures. This poor woman having to live in a world filled with so many knuckleheads.

I saw a Cymbeline recently, a stripped-down version that leaned into the queer readings without actually making them clearer and played pretty much everything for laughs. (Who knew a headless corpse could be so funny!) A couple of the performances were excellent (Nathaniel Andalis in particular was a revelation) but the play mostly wanted to be easy to like. And it was. Perhaps Jupiter should always play the electric guitar.

I've also read long essays about Cymbeline by Stanley Wells and Harold Bloom who have very different takes on the play. I largely accept both their readings (which should upset them both) in part because the play is so strange it's easy to accept all sorts of possibilities.

Of the other strange plays (the problems, the romances, the whatevers), this is my least favorite. But I hope someday to see a production that makes me feel about it as Wells does. Prior to the Victorians, this was one of the more beloved plays. Maybe it can be again.

over a week

109) The Sandman: Season of Mists by Neil Gaiman et al, finished October 5

This is the one (if you'll recall) where Morpheus finds himself in possession of hell. Hijinks, naturally, ensue.

It's a good one.

about a week